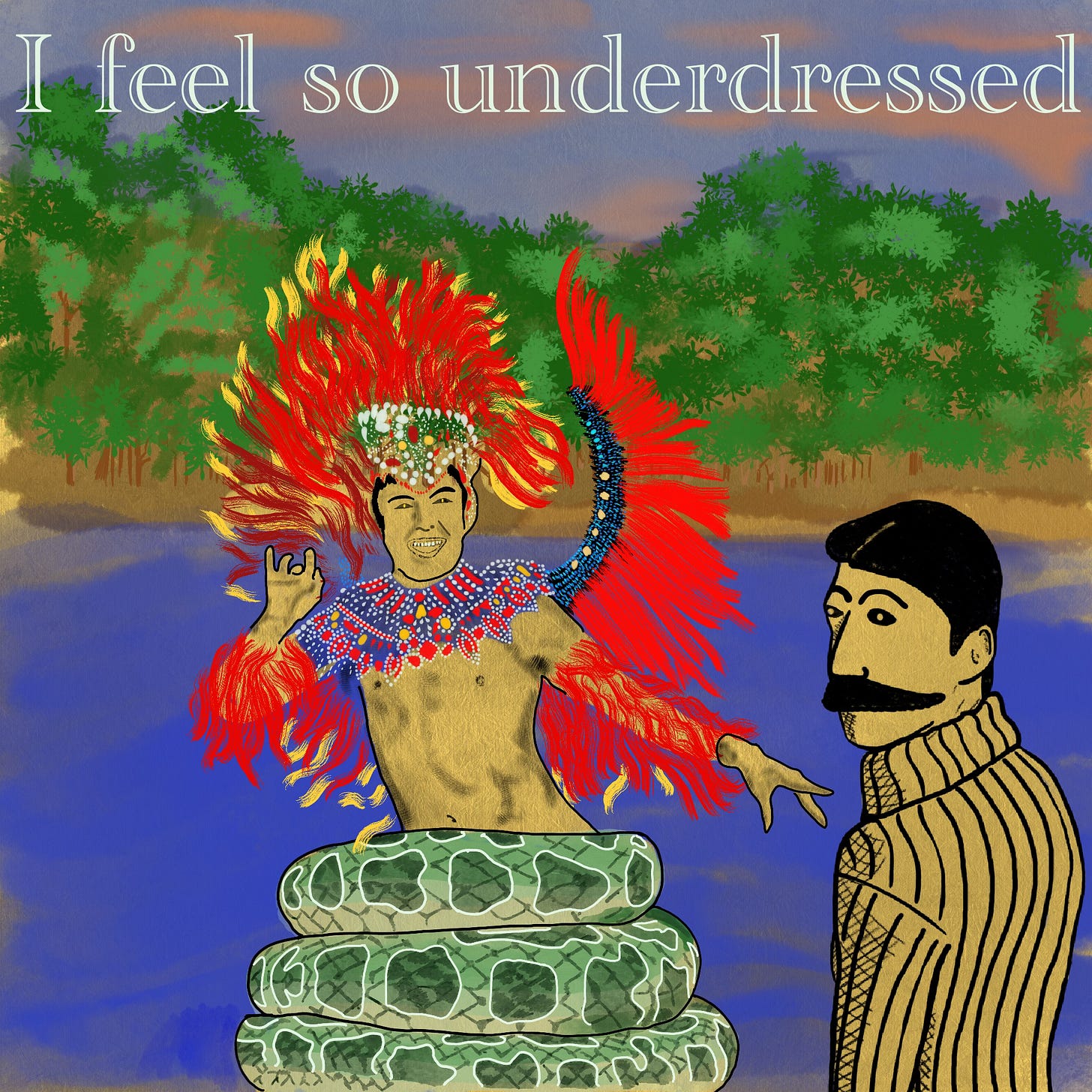

Cobra Norato, The Benevolent Hero Who Learned To Live Between Worlds

Cobra Norato, a Brazilian snake-being who inherited a curse from his mother comes to see his divided identity as the very thing that actually frees him.

This week, meandering down the Amazonian river of time at the heart of the Library of Found Things, comes the inspiring story of Cobra Norato from the Tupi-Guarani people of Brazil.

Deep in the heart of the Amazon, where there are more spirits than there are stars in the night sky, young Mariana was combing her hair by the riverside. Dusk had not yet laid her mysterious light over the veridian canopy of leaves and Mariana was humming a song to herself that caused the waters to stir.

Writhing with the vibrations of Mariana’s voice - bated by its beauty - came the Boiúna, The Keeper Of Secrets, a giant sea-serpent but not always that. Sometimes he is a man, beautiful and alluring. Other times, he takes the form of human boats so meticulously that others of that race follow him into treacherous waters and disappear beneath the shallow waves to the screams of ill-fated sailors.

As the night converged with the day however, The Great Keeper Of Secrets was transfixed and not even he noticed the change coming over him.

Mariana’s voice was hypnotic and the Boiúna slithered into the shallows before he took on the form of the most handsome man the young woman had ever seen. She too was transfixed by his beauty and, instead of running, she continued to comb her hair and hum as she watched the beautiful Boiúna-man kneel before her. As darkness fell, they fell in love and spent the night as lovers do.

Mariana’s family were traditional and they erupted in cries of horror as, nine months later, Mariana gave birth to two small but exquisitely beautiful serpents; a son and a daughter. It’s unknown if Mariana threw the snakes into the river herself or if her family forced her to but what is known is that the daughter, Maria Caninana and the son, Honorato, grew up in the winding behemoth of the Amazon river.

Maria Caninana grew up hard and cruel. She terrorized the human communities by the riverside, she sank boats and drowned any and all humans she could lure into her watery trap. She hated humans and her hatred knew no bounds.

Honorato, however, embraced his dual nature. He grew up to be honorable, kind and understanding of all the creatures that walked the fertile rainforest, including those destructive humans, to whom he owed half his lineage. He took the name Cobra Norato because of his serpentine form and the honorable nature of his heart.

As he matured, he grew out of his snake form and began transforming at night into a most handsome human man. In this guise, he would walk into the communities by the riverside and celebrate their festivals with them; dancing and singing to the delight of all. The women would swoon for him and mourn his absence when, at break of day, he had to return to the river, his soft skin turning to scales as it touched the water.

Norato grew to love his human side as much as his sister devolved into her hatred of her own. She would not change shape, though Norato suspected she could, and she raged as the rapids rage at any sight of humans along the Great River. Norato spent his life moving up and down the same river and he saw that the destruction his sister wrought on the humans had fearful effects on the entire ecosystem throughout the Amazon. He knew the confrontation would eventually come, he knew he would not be able to watch idly as his sister committed great wrongs against Nature. The confrontation came and, though he did not want to, Norato killed his intransigent sister for the greater good.

Norato mourned the loss of Maria Caninana greatly. He saw the hatred she carried as a part of himself, he looked at his serpentine form and saw only her loathing, their father’s absence and their mother’s abandonment. He found himself wanting desperately to become purely human, entirely one thing.

One night, Norato approached a good-hearted soldier of a riverside village and took him into his confidence. He explained that he was torn between two worlds - the river and the land, serpent and human - and he asked the good-natured soldier for his help. The soldier agreed and waited through the night with a large vat of milk by his side. Norato explained that he would transform on break of day and that the soldier was to pour the milk all along Norato’s body, being sure not to miss even a single scale. When day broke and the warm light glistened off the metallic scales of Norato’s body, the soldier was terrified and, in his urgency to run, he knocked over the vat of milk. Norato was devastated and he slithered back into the river.

He wandered the courses of the Amazon, its turbulent rapids reflecting his emotional state. He believed himself truly lost in every waterfall and forever stuck in every sediment bank. He felt neither serpent nor human, neither divine nor mundane and he fell into a deep, deep sleep.

In his sleep, he learned that he could walk and slither between realities. He could slide into the dreams of men, women, and children as easily as he could dance into the minds of jaguars, capybara and dolphins. In their dreams he understood them. He saw himself in all of them and he realised that the tapestry of Nature was within him entirely.

From that day forth, Cobra Norato became a guardian of Nature. All Nature. Flora, Funghi and Fauna … not to mention humans too.

Don’t pretend you’ve never thought snakes could have a sexy side.

Alright, you might not have. That is a bit odd. But you know they’re bloody handsome beasts and you imagined both the Boiúna and Cobra Norato very clearly when they took human forms. Don’t be ashamed of it.

Shame is a slippery bugger, after all. It stops us from doing what we want and locks us in a box under layers of cultural, societal and mystical “so-called norms”.

[Can anyone else hear Dr. Frank-N-Furter singing “Don’t Dream It, Be It”? Just me?? Alright then]

Anyway, whatever ‘inner truth’ a person hides because of their shame is an element of their identity that they are not exploring (sexual, political, even taste in music that some people refer to maddeningly as “guilty pleasures”). The story of Cobra Norato seems to be about exactly that.

You see, this particular version of the myth comes from the Tupi-Guarani people in Brazil. In this region - and many throughout Brazil - the people have had to reckon with the reality of what happens when entire populaces are uprooted, enslaved, dominated and then expected to reintegrate into a society that, in some cases, they had to build themselves out of the broken pieces of a multitude of identities.

The Brazilian anthropologist and historian Béatriz Góis Dantas said this about the state of identity in general but, particularly, that of the Nagô people of Brazil, “Identity is not fixed, but instead, it is negotiated and defined in a variety of contexts in response to sometimes divergent needs.”

Dantas discusses how Afro-Brazilian people have built their own identities through stories, through religion and religious practices that have deep roots in their African heritage but have become something undeniably Brazilian over the many tortuous centuries.

This idea became fundamental to Brazilian identity in the early 20th century in the expressions of Modernist writers like Raul Bopp, who wrote a famous epic poem called Cobra Norato. This, along with Oswald de Andrade’s Anthropophagic Manifesto, were two texts at the heart of a movement in which Brazilians sought to find and formulate their own identity out of a jungle of imperialistic, colonial and distant memories from Africa.

At the heart of the movement was the idea that Brazilians could cannibalise the multiple cultures that had been imposed on them and merge them all together to make something new and positive for their future as a people. Oswald de Andrade not only believed that Brazil’s history of integrating elements of different cultures was one of its greatest strengths but that it was also a way of asserting itself against European postcolonial cultural domination.

Of course, such a movement was not without its detractors. People said that it would trivialise cultural appropriation; that it might romanticise a hurtful stereotype of cannibals, setting the Afro-Brazilian community back further still in the eyes of others; they also said that the writers and artists were from a privileged class and their writing limited the cultural diversity of Brazil at large. These may be perfectly valid complaints with the movement but there was also one that is echoed in the defeatist moans of anti-idealists today: the poetic writings of this movement just offer no practical applicability for modern people.

And this just doesn’t seem right. If you take the myth of Cobra Norato, when he wanders the curves of the Amazon river wondering who he, is he echoes the same questioning nature of any of us at some point in our lives. We are all the products of multiple cultures, whether we recognise it or not.

One parent supports one football team, while the other supports their rivals. Who do we support? We find ourselves falling in love with a gender that society tells us is not the right gender for our gender to fall in love with. Is our love wrong, or perhaps our gender, or perhaps society?

I’m British because I was born in Britain but I grew up in the North West with a family fresh out of Liverpool, a city that often strikes fear and / or loathing into the hearts of those in the ‘South’ where the British Government has its seat. Am I British or an exiled Scouser? The two don’t feel mutually inclusive.

Sometimes we all pick and choose the elements of culture that fit us best, that make us feel at home in ourselves. Since these elements may be from different cultures or times (who doesn’t love a bit of Victorian Chic especially if it includes sexy vampires and a bit of Steampunk?) we invariably adopt a form of that culture, which we inevitably make our own.

Cobra Norato’s exploration of the dreams of the plethora of beings in Nature gives us a sense that we are all multi-faceted and we do not need to conform to anything as fixed and fictitious as any identity a society wishes to oppose upon us. It’s our job to pick up the pieces of the broken identities of the past and forge our own identities for the future not limited by our cultural biases that lead to the likes of nationalism, jingoism and xenophobia.

That’s what I reckon, anyway.