Ragnarok & Happy Accidents

This week we'll be discussing Ragnarok, that most hardcore of myths and how it's actually quite a sweet story of how we need to be more accepting of accidents.

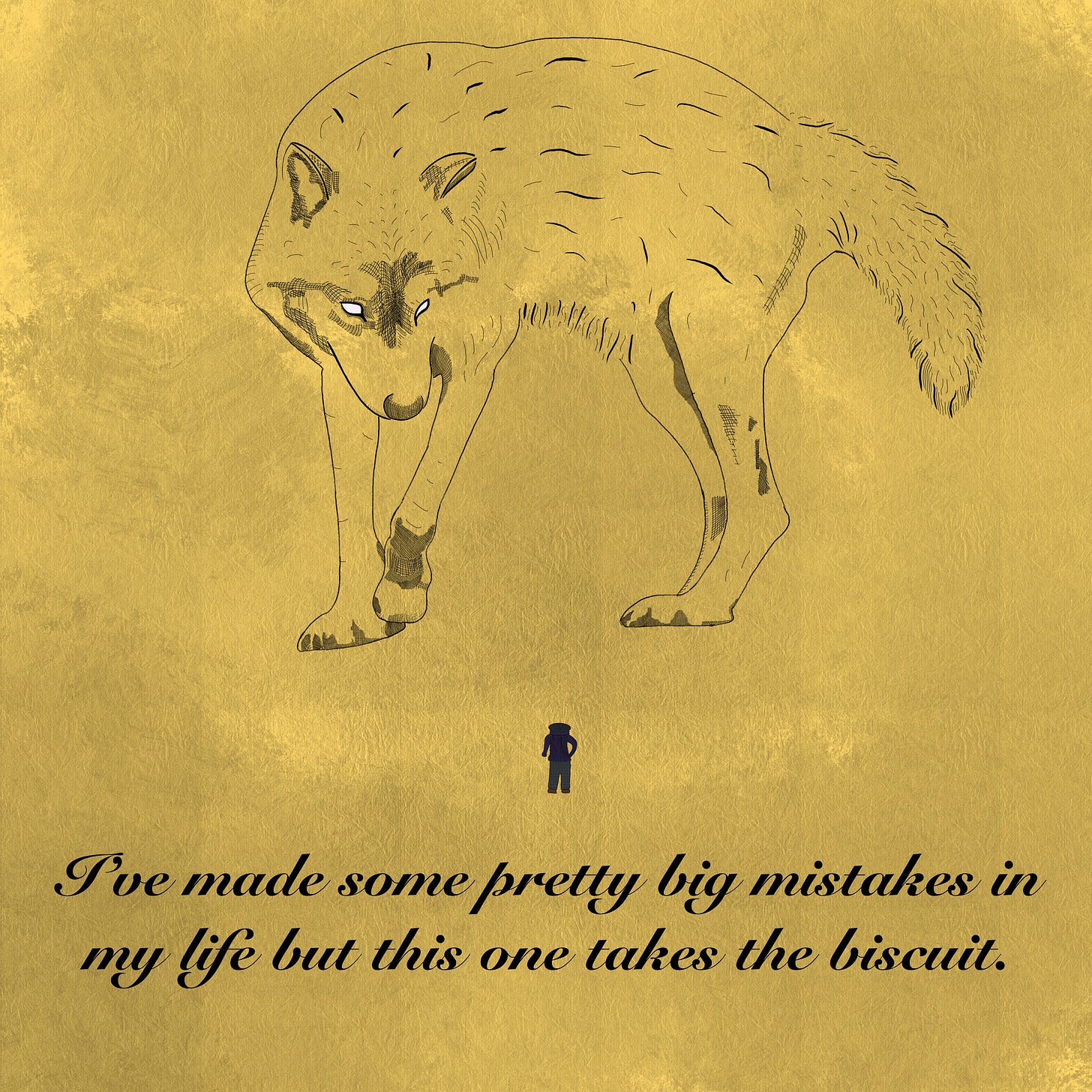

This week, tumbling from the lofty shelves of the Library Of Found Things is a fan-favourite for all mythology lovers out there: The Story of Ragnarok. But this version, rather than focussing on ships made of dead men’s nails, sun-eating wolves and earth-wrenching serpents, focusses instead on a key character whose function in the whole ordeal is fundamental to the sociological / psychological meaning of the entire event: Baldur.

Ragnarok’s Irony

Baldr was the ‘Wisest of Gods’ and, by any metric, everybody’s favourite. However, in the days before Ragnarok Baldur’s dreams were laden with prophecies of his own demise. When his mother Frigg heard this she set about doing everything within her capacity to stop it from happening. So, she decided to impose order on a world.

To do this, Frigg travelled far and wide, demanding every object in the whole world take an oath to do Baldur no harm. Loki, not as an evil-doer but as an ‘agent of chaos’, was disgruntled by Frigg’s attempts to constrain the world. So, he disguised himself as a woman and ingratiated himself - herself? - into Frigg’s inner circle to tease out a crucial bit of information from her that she had hitherto kept to herself. It turned out, you see, that of all the animals, rocks, and plants there was just one that she didn’t exact an oath from: Mistletoe.

The reason? Well, she thought it was ‘too young’ to bother with, apparently.

Meanwhile, the gods had figured out that the oath the world took to protect Baldur had a hilarious consequence: you could hurl absolutely anything at him and it would do him no harm. So, naturally, the gods started taking turns to throw things at their most beloved member.

When Loki arrived - late as always - he asked the blind god Hod why he wasn’t taking part in the fun. Hod reminded Loki of the obvious: he was blind and, therefore, aiming was not his strong suit. Loki said this was nonsense and handed him something to throw and gave him a hint at the direction. It turned out that Hod was a pretty decent shot for a blind god because he hit the bullseye with a mistletoe branch and Baldur fell down dead in a seriously ‘sod’s law’ kind of way that is very popular in myth (think Achilles’ and his pesky heel).

The gods went ballistic and knew exactly whose fault it was: Loki’s. So, they bound him to a rock, put a poisonous serpent above his head to drip burning venom onto him until the end of time. Which was about to come much sooner than expected. More of Baldur’s prophecies came true, Loki eventually broke free and came back with a vengeance to end the world and everything in it.

The End.

Well, not exactly.

Cycles Bloody Cycles

The gods’ reaction to Loki’s mischief, although seriously overboard, is a little understandable given how much they loved Baldur and just how tired they were of Loki’s shit. However, the irony deepens when we look at what Baldur and Loki signified metaphorically.

Baldur’s name is associated with light and the sun. His death is actually a reference to the disappearance of the sun in winter. For people in Northern Europe, for all intents and purposes this was no laughing matter since the sun actually did “disappear” for six months of every year.

It was common in this part of the world to celebrate the summer solstice - the longest day of the year and a chance for miserable smegs to remind you ‘it’s all downhill to winter from here’ - by cutting off a sprig of mistletoe and placing it at the heart of the ceremony. The reason for mistletoe? It’s evergreen! What else would you want to hold onto through winter?

Frigg’s actions, therefore, were to protect the sun but the result of those actions was to betray the ‘natural order’ of things by not allowing the sun to ‘die’. The ‘death’ of the sun is part of the natural cycle that implies the inevitable rebirth of nature itself come spring. What Frigg did was against the nature of things and Loki is, if anything, integrally connected with nature.

The Nature Of Accidents And Accidents In Nature

Now, I’m not about to sit here and tell you, dear reader, what is and isn’t meant to happen. I enjoy a bit of woo woo as much as the next fella but I know about as much of what’s meant to happen as a doornail knows about Dharma, but I can tell you a few things about how important accidents are.

The ancients understood that there were cycles but they also knew the inevitability of accidents. This wasn’t just a misunderstanding of natural science, it was incredibly wise and it plays out on centre stage in the story of Ragnarok.

Loki is an agent of change or, better said, an agent of accident. When Frigg demands an oath from everything in the world she is acting not only in her capacity as a mother (something very easy to sympathise with) but in her capacity as a reginn, an agent of order. In this role, her intention was to impede all accidents in a world full of and dependent on accidents. What happened next? Well, the whole world goes to pot and Loki comes back stronger than before and resentful that his kin tried to make him something he is not. This is some serious ‘Black Sheep Of The Family’ energy. However, this isn’t the version that we get today nor was it the version people read in the main text we have of Norse myths.

Lewis Hyde, in his exceptional book I refuse to shut up about, describes the myth with reference to how it was written down. Snorri Snurlson was an influential Christian who documented the many stories of the Norse gods and, without whom, we would know very little about any of them today. But he was a Christian and that inevitably soured his view of these ‘old’ gods and probably influenced his version towards having some fatalistic ‘end’ of said gods in favour of the coming of his god.

In the original versions of the myth - which we can only piece together through Snorri and other less-complete evidence - Ragnarok did ‘end the world’ so to speak but that wasn’t the end of the gods or even humankind. Two humans, in fact, survived the apocalypse and even Baldur made a return to the divine stage. Lewis Hyde quotes one of the oldest Norse poems not written by Snorri, the Voluspá, in which the prophetess says:

“I see the Earth rise from the deep,

Green again with growing things …

The unsown fields will bear their crops,

All sorrows will heal and Baldr will return.”

You see, this is the cyclical nature of the myth and a justification for letting ‘accidents’ happen in the world because they’re going to bloody well happen anyway and often they can be pretty great! For instance:

Vulcanised rubber was ‘invented’ by accidentally dropping rubber and sulphur on a stove.

Penicillin was ‘invented’ by a lazy scientist accidentally leaving out a dirty petri dish.

Safety glass was ‘invented’ when a French chemist accidentally dropped a glass coated in cellulose nitrate.

The Microwave Oven was ‘invented’ when a scientist working on radar technology for Raytheon accidentally melted a chocolate bar in his pocket.

The Pacemaker was ‘invented’ when a scientist accidentally installed the wrong resistor on a device designed to record heart sounds.

The list goes on!

I doubt it’ll be a surprise to anyone that this is not just a philosophical view, it’s also a fact of nature. It’s at the heart of evolution, for Baldur’s sake, which should give everyone cause for thought. The myth of Ragnarok has this knowledge at its heart and telling the story without it seems to miss the point a little.

Joyful Accidents And The Act Of Resistance

I suppose the meaning I take from this myth is to let go of a little control when it comes to most things in life. An accident can result in the loss of a cup or or worse, true, but accidents are inevitable. It would be just as productive to get mad at your heart for beating as it would to get mad at an accident.

What’s more, by relinquishing control and allowing accidents to happen there’s a chance that you’ll discover a better / faster / sleeker / more interesting way of doing something. When we worry that we’re going to make a mistake we are putting the handcuffs on ourselves. It’s not an argument for carelessness, it’s an argument for approaching the world in a more relaxed and curious manner. As the magnificent Broxh once said, “We don’t make mistakes, we make adjustments.”

So this myth could be seen as a warning against trying too hard to control things. Insisting on categorising everything too strictly and without allowing for accidents, strangeness, difference and oddities to affect the world and make it something truly incredible. As the great writer G. K. Chesterton once said,

“It is one thing to describe an interview with a gorgon or a gryphon, a creature who does not exist. It is another thing to discover that the rhinoceros does exist and then take pleasure in the fact that he looks as if he didn't.”

At very least, I’m going to think about bringing on the apocalypse the next time I call my hand an unmentionable name for cross-hatching in the wrong direction on a wolf sketch.

Your post was a pleasure to read, sparking a fascinating reflection on how, across cultures, mythology personifies chaos as necessary for transformation. I'm reminded of the myth of Persephone in Greek mythology, whose annual descent into the underworld and subsequent return heralds the changing seasons and symbolizes life's enduring capacity for renewal. Moreover, both these narratives beautifully parallel certain Buddhist principles that teach us to embrace the impermanence of life.

What resonates deeply from these tales—and your insightful commentary—is the idea that chaos proceeds transformation or innovation. In embracing the chaos/change/impermanence, we open ourselves to learning opportunities, personal growth, and maybe some profound wisdom. It's a journey that is not always marked by positivity either, underscoring that the path to enlightenment is often paved with challenges as much as it is with triumphs.