The Devil’s Nuts And How To Recognise Them

The Found Story this week is a warning from half a millennium ago of how our presumptions can make us look foolish and how we should be more like a food thief if we're to get by!

Falling from the shelves of the Library of Found Things is a version of a beloved story from Derbyshire, in England but told the world over. This is the story of how the Sexton Carried The Parson.

Around four or five hundred years ago, there was a pair of young men who met in a churchyard one night. The first asked the second where he was going. The second replied that he was hungry and had gone there to pick up some nuts that had been buried under his mother’s head. Presuming she wouldn’t mind her son helping himself to some of her food, the young lad decided to dig into her grave and sate his hunger.

Not seeing anything altogether strange about this, the other young man said that he was just passing through the churchyard to steal a sheep in the next field over. ‘Very good’, said the hungry graverobber, ‘I’ll see you when you get back’, and they went on their separate culinary quests.

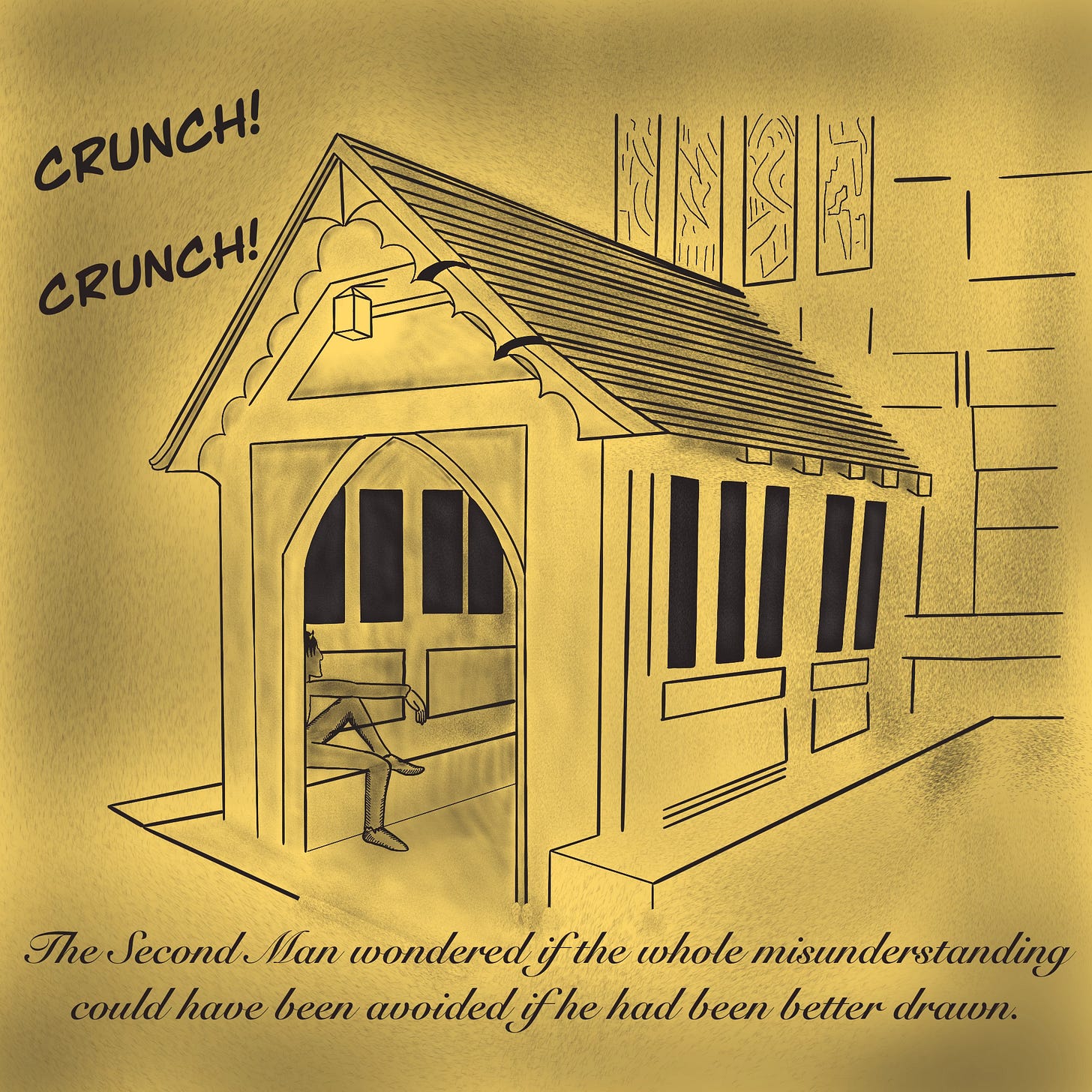

The second man, after he removed the nuts from under his mother’s head, decided to enjoy them in the shelter of the church porch and wait for that stranger to return with a whole sheep.

The moon had taken up residence at its zenith when the time came for the Sexton - whose unhappy job it was to do such things - to ring the evening bell in the church. Before he got close to the holy building, however, he heard a series of unknown crunchings and crackings coming from nearby. Horrified by the ghoulish noises, he turned tail and fled as fast as he could to the Parson.

The Parson, comfortable and warm at his fireside, listened to the Sexton’s tale of bones cracking beneath the malevolent maws of the Devil himself in the graveyard. After listening to the story in the warm light, the Parson called the Sexton a fool for being scared and told him to go and ring the bell anyway. The Sexton was apoplectic and wouldn’t budge from the Parson’s hearth until the Parson came with him. Riddled with gout, the Parson said he couldn’t possibly walk all the way to the churchyard and demanded the Sexton carry him on his back. So, coming to an unhappy compromise for them both, the pair left on the Sexton’s buckling legs.

When they approached the churchyard the unmistakable sound of gnashing and crunching filled the pair with terror and then they heard the Devil speak.

“Is it a fat one?” asked the second young man, seeing the silhouette of a man returning with a large beast upon his back

“Aye and thou canst take it if thou lik’st” screamed the Sexton before surrendering the fat Parson to gravity and running home. Miraculously ignoring his gout, the Parson picked himself up off the ground and fled the scene twice as fast as the Sexton.

The Fool And The Unknown

There’s nothing like a good folktale to remind you of how people have had a sense of humor as long as they’ve had brains. The story of the Sexton Carrying The Parson is actually more of a motif than a myth but if you’ve ever read anything by Joseph Campbell, you’ll know that these motifs crop up all over the world in different stories and that’s what makes them even more human.

This story from Derbyshire has parallels in Ireland, the U.S.A., and even the Caribbean and that kind of spread deserves a little notice.

Now, it’s easy to say that people like funny stories and ones about fat, stupid people who wield power are even funnier. You don’t have to look far for myths, folktales or even modern fiction that ridicules people like the self-important Parson. What’s possibly more interesting about this tale, however, is the other mood it highlights, that of a ‘savvy common person’ pitted against an ignorant person of privilege.

This kind of ‘flipping of roles’ is common in myths and folktales and that tells us a lot about the stories themselves. On this occasion, we have two cunning young lads eschewing any notion of ‘morality’ to find solutions for a very ‘real-world’ problem: they’re a bit peckish.

The reason why a bag of nuts would be buried behind a corpse’s head has been lost today (to the abject sorry of this writer) but the fact that it was buried with the dead suggests that we should treat it with some kind of reverence. Not so the hungry son. This lad looked at the situation and thought, “Well, she’s not going to be needing it where she goes and she never would mind me having a bite to eat on her behalf.”

Contrast this level of realism with the Sexton’s immediate presumption that the sound of nuts cracking in this hallowed space HAD to be the sound of the Devil chewing on bones and you have two very different worldviews setting up the comedy. The hungry son sees through the ‘hallowed reference’ of a churchyard, the church porch and even the quiet of night, while the Sexton is blinded by the many layers of presumption engendered by his faith.

Comedy as an instructive device appears in folklore and mythology all over the world, so when this story falls from the shelves and lands open on the floor of the Library of Found Things, we should really ask what the joke is really all about. And if you asked Mikhail Bakhtin, he’d tell you it was about Carnival!

“Carnivalesque”

Mikhail Bakhtin was a literary critic who wrote the magnificent book Rabelais & His World (1965) in which he expands on his ideas of Carnival and how it relates to subversive literature and thoughts in general.

Much more than just a Christian festival to indulge in meat, cross-dressing (of roles, not just gender) and debauchery before the staid period of Lent, Bakhtin saw in the festival a fundamental human need to shake the foundations of societal power. At Carnival the fool is crowned king, the masters serve their servants, the whole world is put in a topsy-turvy dance and anybody - in theory - is allowed to say anything to and about those in charge.

What’s more, this kind of literature has been cropping up throughout millennia in even the most draconian societies. Aristophanes almost lost his life for making fun of a politician and it could be argued that even Socrates was a Carnivalesque speaker himself. After all, he was killed for ridiculing what most people take for ‘normal society’. Said society simply masked their embarrassment by accusing Socrates of “Creating New and False Gods” in the form of pesky things like logic.

This notion of the Carnivalesque is key to understanding the folkloric motif of today’s story. By ridiculing the Parson, a pressure-release valve of sorts is opened up for the reader. They can place any figure of authority in the Parson’s place too, though at the time of writing / compiling the story there was no shortage of pompous Parsons around Derbyshire.

It’s probably not the most outlandish of assumptions to say that, more than ever, we live in a world where the most miniscule amount of information is snatched up and run away with to all manner of weird and dangerous conclusions. The ‘cracking nuts’ (pun very much intended) coming from the dark porticoes of the internet cause people to hate, fear, curse and cudgel. Given the impossibility of knowing all the facts, we find ourselves acting more like Sexton every day. When, more often than not, knowing all the facts is not as necessary as taking a few extra steps towards the source of the noise and trying to figure out what’s really going on before we attribute it to the Devil.

Ridicule, in the Bakhtin sense, is therefore not only useful but integral to sanity and it’s also a pretty important tool for not falling for the madness the loudest ‘Sextons’ out there try to convince us is normal.

At least, that’s what I reckon anyway.

This and plenty more edifying tales can be found in the exquisite collection edited by Westwood & Simpson The Lore Of The Land: A Guide To England’s Legends if you’re curious.