"The Rebel In The Cave"

After long periods of travel and meeting new people with wildly different views on what I thought was 'reality', I like to fall back on the old stalwart allegories like Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

The word ‘Rebel’ summons images of James Dean and 1970s Rock legends but now more than ever, it’s vital to remember that these images are the products of predetermined perspectives. After periods of travel and meeting new people with different perspectives, I like to lean on the old stalwart allegories like Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

What’s it about?

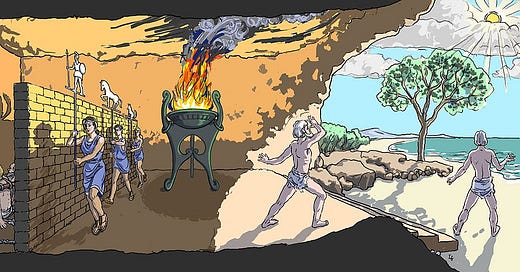

The Allegory of the Cave is a famous allegory written by Plato in his Republic. It describes a nightmarish scenario in which prisoners spend all their lives chained to the back of a cave. They’re chained up in such a way so that they can only see the shadows of things that pass between them and the source of light to their rear.

In most descriptions of this allegory, one prisoner - a rebel, you might call them - somehow becomes unchained and makes their way towards the source of the light.

They come across a number of torches and progressively realise that these are the sources of light they once believed sprung from the rock of the cave wall. They move further towards the cave entrance and are awed by the experience of the ‘true’ source of light, the sun.

When the rebel returns to the prisoners, they talk about all of the beautiful things they’ve witnessed, including the true source of light and the reality of the shadows the prisoners have been watching on the wall.

Rather than breaking themselves free, however, the prisoners greet the rebel’s news with derision and even anger.

We all wanna be the Rebel?

In most explanations of this analogy, the adventurous prisoner isn’t just emancipated from their chains but also from their reality. They’re then presented as “Truth-Knowers” and therefore superior.

Let’s face it, we all think our experiences give us some kind of authority on one subject or another and, in the case of the Analogy of the Cave we all identify with the unchained ‘Rebel’.

As a bald man I could pontificate about the necessity of a good hat for every season to people with flowing locks of warmth-generating/UV-shielding hair without any fear of reproach. But I’d keep my mouth shut and ears poised for any ‘truth’ spoken about how to make the perfect plait.

Perhaps a better approach to this analogy, then, is to force ourselves to identify more often with the chained prisoners?

The Problem with Rebels

The prisoners believe that their reality - their truth - is the ultimate truth. This is common to all of us, especially when the shadows we see on our wall have never failed us yet and, when we’re confronted with a Rebel, our first response is often to look for ‘ammunition’ we can use to shatter their arguments.

In a way, we are all prisoners in our own caves. Our senses are imperfect, our information is lacking. The result of which, if we’re completely honest, is inevitably flawed judgement.

But we know that the Rebel brings new information that could be equally imperfect. What if one of the prisoners was inspired by the Rebel enough to break their chains and venture out of the cave themselves and, once outside, they realise that the Rebel’s “Sun” is nothing more than a car headlamp reflected off a hippo’s highly polished arse?

Do we then dismiss the whole notion of breaking our chains, even if it does allow us to see what all the ‘outside cave’ fuss is about?

The Ultimate Boon

Joseph Campbell talks about one part of The Hero’s Journey called “The Ultimate Boon”. This is the transcendent learning or ‘gift’ that the Hero brings back from their adventure, a gift that benefits society as a whole in some way.

In the case of the Rebel in Plato’s analogy, the Ultimate Boon could equally be ‘ultimate truth’ or just another species of falsehood. So what is the solution? To remain stalwart and reject any ‘truth’ that diverges from our own? Or to remain sceptical but not to the point of rolling a boulder in front of the cave entrance.

We all feel fear of leaving the cave but having left it, seeing ‘The Truth’ does not necessarily mean we are now superior, less so infallible. All it means is that you have something to say, something to add.

What of the hero who returns from their adventure with an ‘ultimate boon’ for society that ends up rocking it to its core? Change, injected into the body politic by a hero or not, is destructive and fertile. Just as the eucalyptus tree needs fire to grow, so too does society.

Even when it is too hot for comfort, it’s vital for society to withstand the heat in order to witness growth. To facilitate that growth will often mean heroes suffer burns themselves and, after witnessing the ‘truth’, society may make a rational argument for dismissing it.

It’s vital to remember that one person’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter, one person’s philosopher is another’s crackpot and one person’s rebel is another’s contagion.

So, what if the “Ultimate Boon” in this analogy is the simple act of stoking the flames of doubt? What if the second Rebel, having witnessed the highly polished hippo’s arse, turns to the first and laughs in their face? At least they would then have witnessed the ‘truth’ themselves and they will have the pachyderm’s wrinkles to prove it.

Would the first Rebel’s return cause an epidemic of doubt so forceful that it would shatter all reality as we know it? Or would it simply introduce nuance to our monolithic state of affairs? After all, the hippo’s arse is reflecting something … it might just be worth taking another look and trying to find the origins of that light for ourselves.

Does this mean we are all to be activists? Chaining ourselves to the local butchers? Not necessarily, activism starts in our depths. Which is especially good for conflict-averse writers like myself.